Stepping up the search for ET

By Bruce Lieberman

The San Diego Union

1-11-07

For Jill Tarter, the revelation came when she was a child walking on a Florida Keys beach with her father.By Bruce Lieberman

The San Diego Union

1-11-07

“I remember just looking and thinking that up there, somewhere around one of those stars, there's another little girl walking on the beach with her dad,” Tarter said.

How could there not be, when the stars in the sky are as common as the grains of sand beneath her feet?

Tarter is now director of research for SETI – the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence. Based in Mountain View in Northern California, SETI is made up of 135 scientists and support staff who have committed their professional lives to searching for signals from extraterrestrials.

SETI is assuredly filled with dreamers. Its scientists have endured decades of skepticism and occasional ridicule as they've listened to the stars. But they've also built a measure of credibility in the scientific world, churning out academic papers and helping to nurture a relatively new field called astrobiology.

SETI's biggest fans are likely members of the general public who devour science fiction novels, and who came of age when films such as “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” and “Contact” filled cinemas across the country.

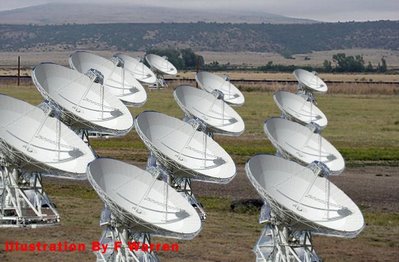

In coming years, SETI will launch its most ambitious search to date. Paul Allen, a co-founder of Microsoft, has bankrolled much of an array of 350 radio telescopes that will be devoted full time to SETI's search.

The $50 million Allen Telescope Array, located at UC Berkeley's Hat Creek Observatory site north of Chico, will search for signals coming from 1 million star systems as far away as 1,000 light-years, or 5.8 quadrillion miles.

SETI is raising money for the project and hopes to complete the array within the next few years.

High-powered computers will automatically scan millions of radio channels simultaneously, digitally analyzing the radio noise coming in to see if anything appears out of the ordinary. (Contrary to the 1997 film “Contact,” astronomers do not listen in with headphones.)

Since the first search for radio signals began in the 1960s, only about 1,000 stars have been surveyed and no unusual signals have been detected.

“Thanks to the march of technology, SETI is poised to succeed,” said Seth Shostak, a senior astronomer with the group. If SETI's assumptions are right – that aliens are communicating using radio transmissions as beacons – then contact should be achieved within a few decades after the array is completed, Shostak said.

Other SETI efforts are under way to search for light signals that stand out amid the glare of stars.

Closest neighbors

So, where is SETI looking?The search is confined to Earth's neighborhood – that is, the stars of the Milky Way.The Milky Way is home to between 200 billion to 400 billion stars and is about 100,000 light-years across, or nearly 600 quadrillion miles.

Other galaxies are simply too far away to make any search meaningful. Andromeda, the nearest galaxy to the Milky Way, is 2.5 million light-years distant. That means that any radio message sent from Andromeda, traveling at the speed of light, would take 2.5 million years to reach Earth.

If humans ever detected a signal, it would be a decidedly one-sided conversation. It's also possible that any civilization sending the message would have died out before its message reached Earth.

“It may be that there are other technological civilizations in other galaxies, (but) the main question in this field is not really whether we're it in the whole observable universe,” said Ben Zuckerman, an astronomer and SETI skeptic at UCLA. “I think most people are asking, 'Are there thousands or tens of thousands of civilizations in the Milky Way, or are there at most a handful – or are we it?' ”

At least in the Milky Way, the only place a SETI search has any real meaning, life may be exceedingly rare – primarily because it seems so difficult to get it started, Zuckerman and other skeptics say.

In the 1950s, physicist Enrico Fermi posed a rhetorical question that went something like this: If aliens exist, where are they? In other words, why haven't we found them?

Since many stars in the Milky Way are much older than our sun, it's likely that alien civilizations – if they're out there – could be millions or even billions of years more advanced than humans on Earth. The galaxy, then, should be swarming with life. Yet there's no sign of it.

Shostak doesn't buy such arguments. SETI has searched only a tiny portion of the Milky Way. Its biggest campaign – Project Phoenix conducted from 1995 to 2004 – surveyed about 800 stars only out to a distance of 240 light-years. The search failed to find anything that resembled an alien signal.

“That doesn't discourage me at all because that's such a tiny sample,” Shostak said. “It would have been rather surprising if we had found a signal that quickly.”

Some findings have encouraged SETI scientists. Over the past 15 years, astronomers have discovered more than 200 planets outside the solar system, orbiting other stars. Scientists have estimated there may be 6 billion Jupiter-size planets in the galaxy.

Future spacecraft are expected to actually take pictures of extra-solar planets, but it will probably take many, many years – if it ever happens – to estimate confidently what fraction of stars in the Milky Way has planets.

Zuckerman is unimpressed with the discovery of extra-solar planets, as it relates to SETI's search for intelligent life.

“I don't think anybody really doubted that most stars would have planets around them, and this is just sort of confirming that,” he said. The planets discovered so far, he added, appear to be huge gas giant planets, similar to Jupiter or Saturn. “They seem to be rather unpleasant places (compared with) terrestrial planets like the Earth.”

On both sides of the SETI debate, scientists acknowledge that what's certain is the limit of what they know.

“I personally think that because the origin of life is an extremely difficult process. . . even simple life is very rare in the galaxy,” Zuckerman said. “But I have no particular claims other than my gut feeling.”

Shostak has publicly debated Zuckerman on the issue, and he remains confident that future searches will make contact. “I doubt that I would conclude that nobody's out there,” he said. “To me that seems like a last resort option. But that's simply my feeling on the matter. And my feeling on the matter . . . actually means nothing because what counts is what you can find.

“That's the difference between science and belief.”

Promise of progress

Certainly, the question of life beyond Earth is one that captivates scientists around the world.“I think it's one of the most important questions in science, undoubtedly,” said Martin Rees, the renowned British astrophysicist and author. “The reason I don't spend most of my time working on this is because I don't think I can make any progress. When you're a scientist, you work on problems which you think you can make progress with.”

What keeps Shostak motivated, however, is the promise of progress. Astronomical discoveries and advances in engineering and computer science are setting new directions for their search.

More discoveries of planets orbiting other stars by ground-based telescopes and planned orbiting telescopes will help SETI refine its search to the most promising targets. The Kepler spacecraft, due to launch in 2008, will continuously monitor the light from 100,000 stars to see whether Earth-size planets are orbiting around them.

At the same time, the Allen Telescope Array will cast a much wider net into the cosmos and expand the search dramatically.

“That's actually the most exciting thing about SETI – that we're speeding up the experiment all the time,” Shostak said. “Whatever experiment we're doing this year is usually better than all the previous years put together. Things get faster. That's what technology gives you.”

For Shostak, like Tarter, inspiration came early.

As a child, he was enthralled by visits to Hayden Planetarium in New York City and built his own telescope when he was 11. Years later, as a graduate student in the late 1960s, he spent long hours at Caltech's Owens Valley Radio Observatory studying galaxies and the dynamics of their rotation.

During a 3 a.m. break from one of his observing sessions, Shostak began reading the 1966 text “Intelligent Life in the Universe” by I.S. Shklovskii and Carl Sagan. It was one of the first formal treatments of the scientific and technical issues surrounding the SETI search.

The book hit Shostak like a bolt of lightning.

“That the very instruments that I was using to study galaxies could also be used to communicate between the stars was a very romantic idea,” Shostak said.

He met Tarter more than a decade later, and he formally joined SETI in 1991.

“If we were to find that we're not the only kids on the galactic block, that would be a discovery of everlasting interest and importance,” Shostak said. “It's a privilege, really, to be able to work on a project that addresses such a big picture question.”

Not everyone is convinced. The late Sen. William Proxmire campaigned for years to keep SETI out of NASA's budget, and critics have long joked that the group's scientists are obsessed with finding little green men.

“We worked very hard to overcome the kind of flaky and fringy stigma that we started with, and we did it by doing the same things that you do with any science,” Tarter said. “You make the presentations, you write papers in peer-reviewed journals, you go and you do your observations, (and) you build equipment that nobody's built before.

“When people say, 'Oh that's ridiculous,' you say, 'Damn it, this is a scientific exploration. It's not UFOs, it's not UFOs, it's not UFOs.' We've had that mantra.”

About half of SETI's $16 million budget today comes from NASA, in the form of competitive research grants. The space agency is expected to cut its budget for astrobiology research by half, however, so SETI in October announced a new private fundraising campaign.

Find, then decipher

If humans detect a signal, it's hard to say what that day will be like.“I don't think there will be panic in the streets,” Shostak said. “You have to remember, we're picking up a message coming from hundreds, maybe even a thousand light-years away. They're very far away, and they don't know you've picked up the signal.”

Surely, anyone with a telescope will be out that night looking toward the place where the message originated.

It's possible we could receive a message and never figure out what it says. The discovery might be akin to the Incas 500 years ago finding a pile of books washed up on their shores, Shostak said.

“They're not going to understand them, but they would know there's somebody on the other side of the ocean,” he said.

“I think it's unlikely we'd understand (an alien signal), but I do think it would change everything.”

No comments :

Post a Comment

Dear Reader/Contributor,

Your input is greatly appreciated, and coveted; however, blatant mis-use of this site's bandwidth will not be tolerated (e.g., SPAM, non-related links, etc).

Additionally, healthy debate is invited; however, ad hominem and or vitriolic attacks will not be published, nor will "anonymous" criticisms. Please keep your arguments/comments to the issues and subject matter of this article and present them with civility and proper decorum. -FW